A Conversation with Eric Goralnick: Facilitating Translation of Emergency Care Innovations in Military and Civilian Communities

Trauma is the leading cause of death for those under 45 years of age, and Eric Goralnick, MD, MS, is focused on addressing this deadly public health crisis. The two-time Innovator Award recipient, Stepping Strong Emergency Medicine Advisor, and Navy veteran is addressing the challenge by focusing on the bidirectional translation of emergency care innovations between the military and civilian medical communities. Donna Woonteiler spoke to Goralnick about his efforts, both here in Boston and worldwide.

DW: Thanks for talking with me today, Dr. Goralnick, and for your recent just-in-time educational video that empowers Ukrainians impacted by trauma to stop uncontrolled bleeding. For many years, you have been a STOP THE BLEED® researcher, trainer, and advocate. How did this initiative start, and why is it necessary?

EG: The birth of STOP THE BLEED started overseas on the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq. Over a decade, the military trained and empowered soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines to recognize life-threatening bleeding, apply pressure, pack a wound, or apply a tourniquet. Pre-hospital hemorrhage control, intervention, blood transfusions, and rapid prehospital transport reduced deaths by 44% on the battlefield, which equated to thousands of lives saved.

“Over a decade, the military trained and empowered soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines to recognize life-threatening bleeding, apply pressure, pack a wound, or apply a tourniquet. Pre-hospital hemorrhage control, intervention, blood transfusions, and rapid prehospital transport reduced deaths by 44% on the battlefield, which equated to thousands of lives saved.”

DW: At what point was a concerted effort made to translate the success of the military to the civilian world? And can you comment on how long it takes for someone to bleed to death?

EG: We can trace it back to December 2012, when 20 children and eight adults were tragically killed in the Sandy Hook shooting. Lenworth Jacobs, MD [keynote speaker, 2020 Stepping Strong Symposium], was head of trauma surgery at Hartford Hospital when Sandy Hook happened. His response to the tragedy was to convene the “Hartford Consensus”: a small group of trauma surgeons dedicated to applying lessons learned from combat casualty care.

One year later, the Boston Marathon bombings occurred. On that fateful day, 30 individuals, including Gillian Reny, survived because of life-saving care applied in the field, either by Boston EMS or by laypersons. That showed us that civilians would step up to render aid in a crisis setting.

From that point, many campaigns focused on layperson empowerment, including STOP THE BLEED, which became a White House initiative. Similar initiatives such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), automated external defibrillators (AEDs), and opiate reversal (Naloxone) also empower the public to step up and save lives.

Regarding your question about bleeding to death, timing is a crucial factor. On average, it takes seven minutes for EMS to respond to a call. If the hemorrhaging isn’t stopped, a person can bleed to death in just five minutes. And if their injuries are severe, this timeline can be even shorter.

DW: What are some of the challenges in training laypeople as first responders?

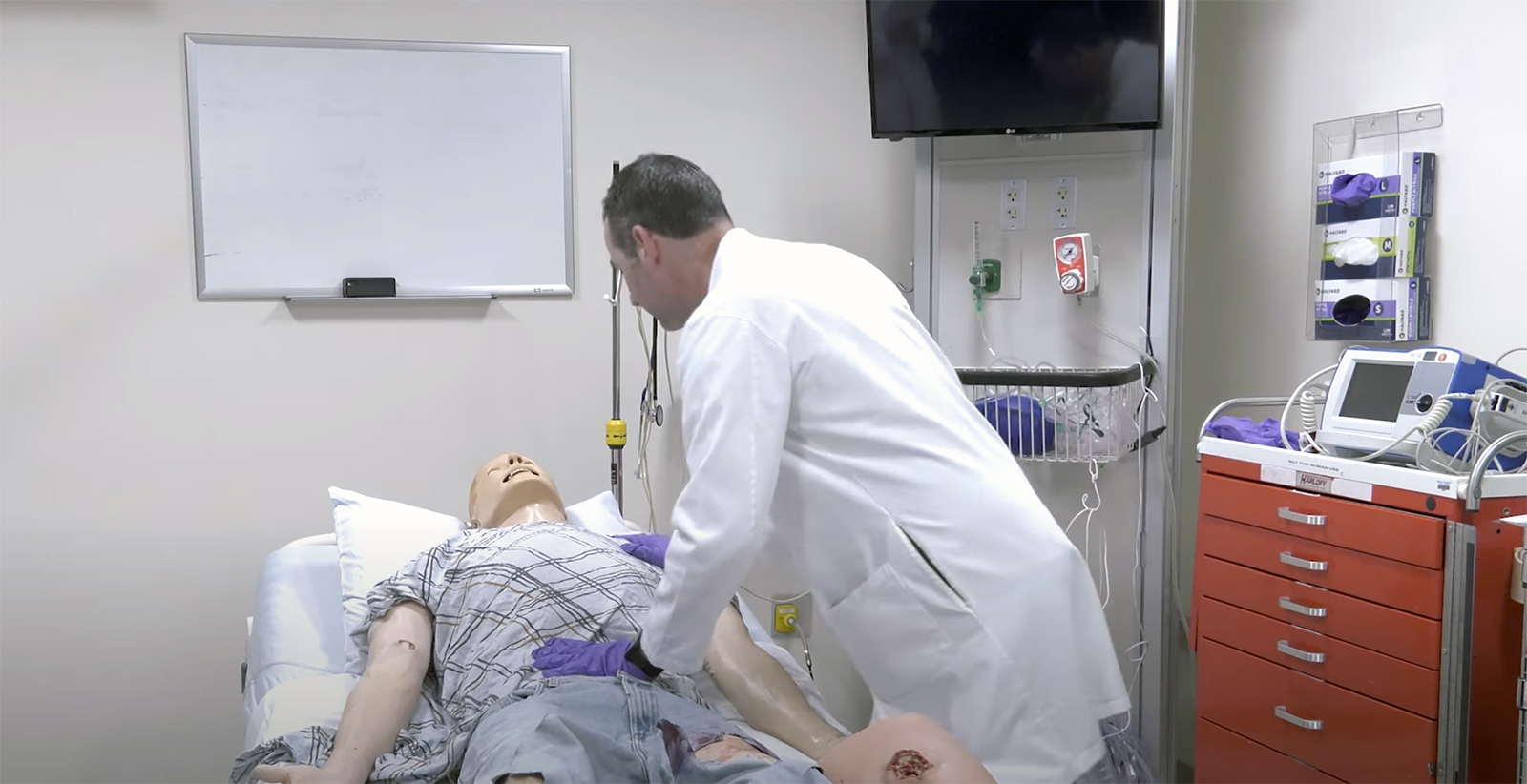

EG: Two things: training enough people and ensuring they retain skills. In our first large study, the PATTS [Public Access and Tourniquet Training Study] trial, we demonstrated that 92% of participants with no medical background could apply a tourniquet in the right amount of time, in the right location, and with the right amount of tension. After the one-hour Basic Hemorrhage Control (B-Con) course, approximately 55% of people retained those skills three to nine months later.

We found in a later study that despite taking the B-Con course, participants were significantly less likely to correctly use another type of tourniquet not taught in the class.

DW: Tell me about the conference you convened to address these continued challenges.

EG: Sure. In 2019, the Stepping Strong Center and the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health hosted the National Stop the Bleed Research Consensus Conference. Over two days, 45 national experts defined a consensus-driven agenda to guide pre-hospital hemorrhage control research for the next decade. One topic–equipment and supplies used to control hemorrhage—emerged as a significant concern given the number of tourniquets available to the public, ease of use, and lack of standardization.

This underscores the challenges of a free open industry, which is excellent because it allows you to foster innovation. We are working with the Uniformed Services, the University of Health Sciences, and the Department of Defense, and we now have funding to develop a novel audiovisual tourniquet that includes real-time instructions. The simpler, the better. Some pilot studies are promising, and we’re doing a large-scale study this fall.

DW: Can you say more about simplifying the process? What model might we emulate?

EG: The pandemic has pushed innovation in education. A good example is the AED, but even more innovative are phone-based applications, videos, and other short, visual resources that can educate or guide actions “just in time.”

“Our goal is not only to train laypeople to stop uncontrolled bleeding but also to empower them to save lives.”

And that takes me to another critical point. Our goal is not only to train laypeople to stop uncontrolled bleeding but also to empower civilians to save lives. For example, cardiac disease is one of the leading causes of death in the world. Communities with comprehensive AED and CPR [Cardiopulmonary resuscitation] programs have achieved survival rates of nearly 40% for cardiac arrest victims. Similarly, I know you talked with Scott Weiner about reducing opioid deaths by teaching Stepping Strong community partners how to administer Naloxone.

There’s so much opportunity—but again, we need to continue simplifying these tools to make a significant impact in preventing the loss of life.

DW: What if you had all of the necessary funds to achieve these objectives in the next few years? What would the future look like?

EG: We would commit to a series of trials with like-minded partners to develop, test, and improve just-in-time tools until we hit a tipping point in which those tools were consistently effective. At the same time, we would advocate for local, state, federal, and international policies so the tools were deployed equitably around the globe.

DW: Thank you so much for talking with me today, Dr. Goralnick. Any last thoughts?

EG: I am so grateful for the Stepping Strong Center’s support and leadership in advancing trauma care. The time, commitment, passion, and investment that the center demonstrates every day contributes to lives saved.

Eric Goralnick, MD, MS is an associate professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a practicing emergency medicine physician. Goralnick is the faculty lead for the Harvard Medical School Civilian Military Collaborative and the Brigham’s Center for Surgery and Public Health emergency medicine initiatives. A U.S. Navy veteran, his research focuses on trauma care, emergency preparedness, leadership development, and operations management. Goralnick is a graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University, Yale New Haven Hospital Emergency Medicine residency, and holds a Master of Science in Health Care Management from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He currently serves as Chair of the American College of Emergency Physicians Section of Disaster Medicine.